BOOK REVIEW: A lifetime of crisp observations and insights

ROME — A Word in Edgeways by long-time Rome-based Australian writer Desmond O’Grady provides a rich and varied range of interviews, literary criticism and profiles that O’Grady has produced over his many years as a foreign correspondent in Italy.

For the most part the articles and essays are gems — sharp, clear, with flashes of brilliance. The title of the collection is apt — O’Grady doesn’t spend much time laying down background and context for the reader. Instead, the pieces generally presume a longer conversation already underway, whether it be about James Joyce’s Trieste or Gabriele D’Annunzio’s “temple of kitsch” Vittoriale, with O’Grady interjecting his own crisp observations and insights before retreating from the scene.

The first half of the book is more intimate and revelatory of the author. We read about O’Grady’s writerly aspirations as a young man from Melbourne and of how he landed in Rome – like many ex-pats, with the expectation of a sojourn short and sweet – and ended up staying the better part of a lifetime. (Love and work.) “Desmond and His Doppelganger” is a charming and very funny account of the decades-long confusion the author suffered through with the womanizing Irish poet of the same name, who also resided in Rome for a time.

Other essays include reflections on the spiritual vision of writers such as Katherine Mansfield (who like many Anglo Saxons before the invention of antibiotics put her last hope for recovery from tuberculosis in the gentle climes of Italy – alas, to no avail) or confessions of a literary infatuation with the shifty Curzio Malaparte. There are also musings of a more private nature. O’Grady devotes several tributes to fellow Rome ex-pats, now deceased, where he writes with great affection and tenderness of their twilight in Italy. I was also touched by his essay comparing his own ex-pat writing preoccupations to those of fellow Australian writer Gillian Bouras, who wrote from Greece and had a tormented relationship with her adopted country.

The second part of the book consists of interviews with present-day authors and artists (some now dead), most of whom have some Italy or Europe connection. Here, O’Grady is no longer injecting “edgeways” into the conversation, but handing it over to his subjects. Indeed, most of the profiles have the feel of transcribed recordings, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The voice of each writer – from a surprisingly optimistic Doris Lessing to a delightfully fulfilled Shirley Hazzard – comes through strongly and the faint presence of the interviewer is a refreshing change from so much celebrity profiling these days, where journalists seem to feel the need to impose their own burdened narratives.

The incisive, eloquent voice of Venice crime writer Donna Leone, whom I’d dismissed as a mediocre writer, made me want to try her again. Diane Johnson, author of the Paris-set Le Divorce, on the other hand, comes across as having a superficial understanding of French culture and being jaw-droppingly out of touch with the social tensions of France today. (“In France, Muslims from Africa feel integrated – at least they did until recently. It has made a better fist of assimilation,” she says.)

O’Grady even has fun with interviews that flopped, recounting how he left a drunken and drugged mess of a Tennessee Williams in his hotel room in Rome, as the writer whimpered to his assistant, “What went gone wrong?”

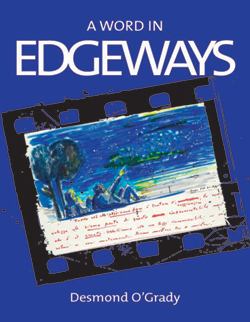

Any shortcomings of this engaging collection are in form, rather than content. None of the essays, written over a span of decades, one assumes, have a date provided, so context is even more difficult. Also, at a time when competition for book sales is ferocious and publishing as we know it is on the brink of implosion, it seems an act of willful self-sabotage on the part of Australian publisher Connor Court to produce such an awful, out-dated looking book cover. (It turns out to be a water colour by Fellini, but it could well have been the first work of a 12 year old dabbling in paints, given the low-quality reproduction.) Equal attention, namely none, was given to proof reading the book, which is riddled with punctuation typos. Publishers are strapped for cash, true. Yet a proper proof-read or a cover designed to draw in the thousands of readers curious about Italy and Europe-based writers would not only have given due respect to O’Grady’s fine writing, but also sold more books. Whether we like it or not, books are judged by their covers. This is why I urge potential readers not to be put off by this one — its pages hold small treasures.