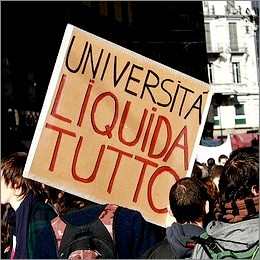

Italy university barons "deserve austerity"

VERONA - In July 2005, I argued that the Italian government should cut the cash it hands out to Italian Universities - Mario Monti’s government did just that.

On Dec. 19, the Italian Minister for Higher Education, Francesco Profumo warned that the cuts in funding threatened to push half of Italy’s universities into default. Three hundred million euros are needed, he claimed, while only 100 million is allocated in the budget which was passed before the Mario Monti government resigned.

Echoing the Minister’s fears, Marco Mancini, president of the Conference of Italian University Rectors, said there was a the risk of the “collapse of the system”. It is impossible to have a meaningful conversation about the Italian University system without talking about - “raccomandazioni” - a form of corruption concerning the handing out of jobs to friends and family. It is endemic to Italy.

Translating this word is challenging; “recommendations”, will not do since these are official and above board. Clientelism, nepotism and cronyism take us some way, but these vices exist to a greater or lesser extent in any culture. What sets raccomandazioni apart is that this practice is the rule in Italy, and not the exception, when it comes to the recruiting of teaching staff.. The granting of tenure pre-supposes that the candidate appointed has a raccomandazione already in place without which he would not have the impertinence or stupidity to apply for the post in the first place.

Every single person working in every single Italian university knows this, all will talk about it in private, few in public. The recruitment is done through concorsi - again, inadequately translated as “open competition exams” which, if I may paraphrase Voltaire on the Holy Roman Empire, are neither open, a competition nor an exam, since the outcome is pre-determined. Needless to say professore can hardly be translated as professor, since in the rest of the industrialised world the latter are employed on the basis of meritocracy, which is anathema to the Italian system. In 1998, Luigi Berlinguer, then Minister for Higher Education, rather coyly admitted to the problem - when he said that Italian universities have “no tradition of evaluation”.

Less reticent is Roberto Perotti, professor of economics at the private Bocconi University in Milan and author of L’Università Truccata (The Rigged University) who noted that “In some of Italy’s state university departments 30 per cent of the staff have a close family relative present. This is nepotism and corruption, and it’s everywhere”. It would be a mistake however, to think that all professori share Perotti’s disapproval. In February 1998, at a public meeting of foreign lecturers “lettori”, in Bologna the former director of Florence University’s language teaching centre, Cesare Cecioni told the assembly, “It seems you have still not understood that tenure has nothing to do with teaching: it rather concerns the privileges that a professor enjoys. If you were to apply for promoted posts you would have no chance of success. As we would be judging you, it would simply be the slaughter of the innocents”.

The consequences of such corruption are obvious. In the Times Higher Education Supplement World University Rankings 2012-2013 not a single Italian University makes it into the top 250. If we look at the statistics for Europe not a single Italian University is in the top 100. In the European top twenty, 8 are in the UK whilst in the Netherlands with a population of 16 million as opposed to Italy’s 60 million, there are 4. Even in times of plenty it would be grotesque to feed such a spectacular failure. Interviewed in 1998, the late Indro Montanelli, a journalist and one of Italy’s most respected social commentators, admitted that it would be logical but not viable to pension off the 58,000 professori and bring in non-Italian exam commissions to appoint replacement staff. Honesty, he said, would prevent him from advising Italy’s youth to stay and fight the system, since, he added, they cannot succeed in eliminating Italy’s university scandal and its 300 year old backward culture. The European Community’s Erasmus programme – which allows for students to complete part of their studies abroad – is already undermining Italy’s universities.

My students come back from the UK and Ireland transformed. Not one has ever favourably compared his life as a student at home with his experience of a university abroad. In terms of success, Italians abroad have always had an impressive track record. Given the correct opportunities, they flourish. As Italian universities go to the wall, the option of studying abroad will become more and more attractive.

This would be nothing more and nothing less than an indication that the single market is working. I have some sympathy, but not a lot, for Marco Mancini, complaining that cuts are especially damaging because of their indiscriminate nature. The universities themselves have had years to reform and become more competitive, yet have shown little willingness and even less ability to do so. This takes nothing away from his good intentions and those of the hapless ex-Minister Profumo.

The universities, bankrolled by their paymaster, the Italian state, have for almost 30 years been fighting an expensive and unseemly war against its foreign lecturers, who still have to sue to get their wages paid (my lawyer filed my umpteenth law suit just before Christmas). To justify not paying us the wages deemed fair and equal by the European Court of Justice, a fiction has been mounted to the effect that we sit around language laboratories correcting students pronunciation.

Purpose build ghettoes called “linguistic centres” have been put in place to separate the foreign teachers from the Italians. The results are Chaplinesque – with students running from one lesson with the native speaker to another building for lessons in the same subject with the Italian professore. This circus is kept alive with the native speakers “testing” the students’ competence and forwarding the results to the administration for delivery to the Italian professore who carries out another test which is not called a test but an “exam”. It renders parody impossible.

As one Italian professor told me in the corridor, we have tried to fregare (screw) the lettori but have ended up screwing our own students. Who in their right mind would throw more money at the ring-masters that run Italian universities?

David Petrie is head of the Association of Foreign Lecturers in Italy ALLSI. (Dis)integration of Mother Tongue Teachers in Italian Universities: Human Rights Abuses and the Quest for Equal Treatment in the European Single Market , by David Petrie is published Jan. 15 in Native-Speakerism In Japan: Intergroup Dynamics In Foreign Language Education, eds, Houghton and Rivers, Multilingual Matters Ltd, Clevedon/UK

PETRIE

Cesare Cecioni

When I wrote this for Italian Insider I was unaware that Cesare Cecioni whom I quoted as follows: “ It seems you have still not understood that tenure has nothing to do with teaching: it rather concerns the privileges that a professor enjoys. If you were to apply for promoted posts you would have no chance of success. As we would be judging you, it would simply be the slaughter of the innocents”. had passed away on 12 September 2012. Maurizio Gotti announced this in a circular to AIA Associazione Italiana di Anglistica, his tribute Cesare Cecioni and those of Giovanni Iamartino, Stefania Nuccorini, Marina Bondi, Giuliana Garzone, Pina Cortese, Rosa Maria Bollettieri, Paola Evangelisti, Carmela Nocera, Gabriella Di Martino, Marina Dossena, Gabriella Del Lungo, Carol Taylor and Gigiola Mariani can be read at pp. 20-22 of the Association’s Electronic Newsletter n. 70 – November 2012. David Petrie